Is Drupal a Disruptive Technology?

Drupal’s founder, Dries Buytaert, in his keynote at the 2010 San Francisco Drupalcon, asked the rhetorical question: Is Drupal a disruptive technology?

The term, “disruptive technology,” was coined by Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen and popularized in his bestseller, The Innovator’s Dilemma (ISBN 0-06-662069-4).

In its lowest terms, a disruptor enters a marketplace with an alternative technology and “kills” the leader(s).

But killing the market leader is not easy. The leader will defend its leadership position in the market. That strategy is called, simply, “defense.” Almost always leaders easily beat-back challengers because the leaders have the motivation and the resources — know-how, talent, organizations, capital reserves, and client relationships — which entrants must more or less replicate. The entrant must overcome what business schools call the barriers to entry. Yet sometimes leaders are toppled. Just last year, the American auto industry collapsed. GM and Chrysler faced bankruptcy. Were American automobile manufactures leaders any longer?

Leaders

Who can rightfully be called a leader?

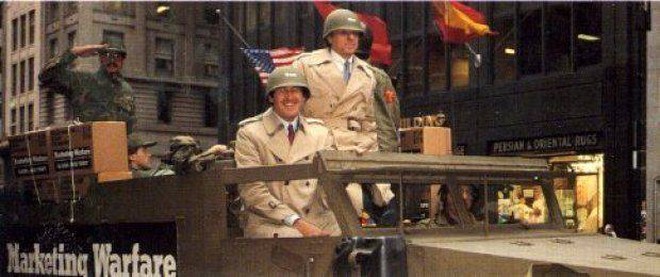

In their classic book, Marketing Warfare, (updated and reprinted in 2006, ISBN 0-07-146082-9) co-authors Al Ries and Jack Trout observe,

We’ve never met a company that didn’t consider itself a leader. But most companies base their leadership positions more on creative definitions than on market realities. Your company may be the leader “east of the Mississippi on Monday morning,” but the customer doesn’t care. Companies don’t create leaders—customers do.

Market leadership is not linked just to dollar volume, either.

Size, of course, is relative. The smallest automobile company (American Motors) is considerably larger than the largest shaving company (Gillette). Yet American Motors should fight a guerrilla war and Gillette should fight a defensive war. What’s more important than your own size is the size of your competition. The key to marketing warfare is to tailor your tactics to your competition, not to your own company … … history teaches the power of a guerrilla movement. In business, too, a guerrilla has a reservoir of tactical advantages that allows the small company to flourish in the land of the giants.

So, there is hope for players, other than giants.

The Lay of the Land in Brobdingnag

Actually, the Ries-Trout model lays out four segments, each one relative to the other players in a specified market:

- Defense — leader

- Offense — challenger

- Flanking — dark horse

- Guerrilla — niche player

Christensen’s disruptor, at least in the early stages, does not fit into the role of a leader (defense) nor challenger (offense). Rather, the disruptor better fits the definition of either a “guerrilla” or a “flanker.” The advice Ries-Trout give each of these categories, respectively, is:

Guerrilla:

- Find a segment of the market small enough to defend.

- No matter how successful you become, never act like a leader.

- Be prepared to bugout at a moment’s notice.

Flanking:

- A good flanking move must be made into an uncontested area.

- Tactical surprise ought to be an important element of the plan.

- The pursuit is as critical as the attack itself.

Strictly speaking, the Ries-Trout model is marketing focused — positioning, if you will — while the Christensen model is technological innovation focused. For example, the Ries-Trout analysis aptly applies to brand battles among beers, among colas, and among hamburgers; and while lite beer might be a “technological innovation” of sorts in the “beer wars,” it is not epic in the way that transistors displaced vacuum tubes in the electronics industry. On the other hand, when it comes to handheld devices, the battle for the hearts and minds of consumers can be addressed by both models — brand and technology.

Flanking moves must be made into uncontested area.

With this in mind, let us look at Christensen’s concept of a disruptive technology.

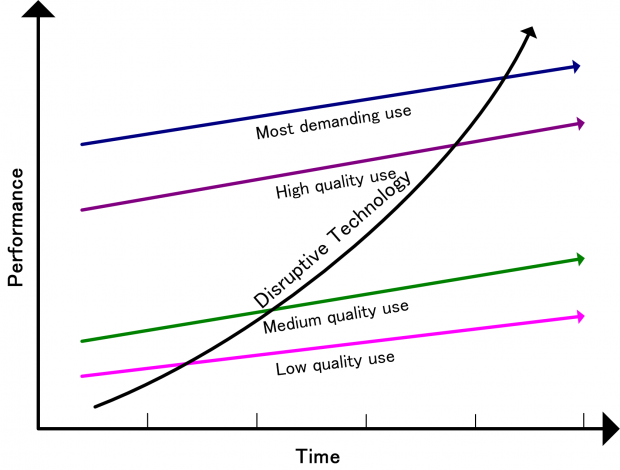

A disruptive technology provides a product or solution that is not quite good enough; it is a technology that enters the market at the low end where expectations are modest, or even non-existent — often competing against non-consumption.

An entire class of low-end electronic products came from Japan in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1950 the label, Made in Japan, was synonymous with poor quality. Thirty years later it meant cutting-edge — top quality. The crummy transistor radio that teens bought in the 1950s gave way to state-of-the-art transistor-based electronics in many fields — televisions, audio equipment, cameras, copiers, and cars. Christensen points out that in the 1950s, transistor-based technology was on the “radar” of the big American electronics manufacturers. The leaders used vacuum tubes to run the electronic systems. The leaders knew transistors would eventually replace the vacuum tubes, but at the time the transistors were not powerful enough to run the large console televisions and console home entertainment systems. In 1975 the head of General Electric research addressed Professor Richard Rosenbloom’s “Management of Technological Innovation” class at the Harvard Business School. He was asked by students why GE had not developed computers. Computers would seem a “natural” for GE. In part the reason was that IBM accounted 25% of GE’s vacuum tube business. GE wanted to profit from that business and did not wish to alienate IBM. Nevertheless, the leaders in electronics, according to Christensen, invested the equivalent of at least $3 billion of today’s dollars in transistor technology, hoping to make transistors good enough to run the console-sized systems. The Japanese transistor radios were not created to compete with the consoles. They found a niche among teens who could listen to their kind of music on something they could afford. Transistor radio performance was not as good as the expensive upmarket consoles, but the consoles were largely controlled by grownups who usually would police what got played. For the teens, essentially it was the transistor radio or nothing. The alternative was non-consumption. The leaders in the market did make some transistor radios, but they largely left the market to Sony, and others, who targeted the low-end market, and in this way the entrants established a beachhead, from which they worked their way upmarket.

Disruptive Technology is not a technology problem

Professor Christensen recounts that shortly after the Innovator’s Dilemma was published, he gave a top level presentation to Intel management in which he introduced the concept of disruptive technology. It was Andy Grove who pondered briefly, then said that it was not the technology that was disruptive, but the marketing that was disruptive. In another lecture, Professor Christensen observed, in the case of the vacuum tube manufacturers, that the electronics market leaders had framed transistors as a “technology problem” — i.e. as a technology that would replace the vacuum tube, outright. As described above, the Japanese transistor product was not framed as a technology problem. Instead, it was sold for what it was — i.e. hence a marketing strategy.

In another example, in 2007-2008, Professor Christensen describes a very low-end, low-cost, solar technology developed at Hewlett-Packard (HP) that could barely run a light bulb. The idea for using it for a product first found acceptance in not-yet industrialized countries in locations that have no electricity or appliance that need electric power. Again, competing against non-consumption. In 2010, the HP technology is being developed to provide solar power to wrist watches, and likely a host of other applications. The technology developed for the non-industrialized world finds a host of uses worldwide.

Christensen gives example after example of technologies that mirror that model — technologies that entered down-market in undemanding applications — again, competing against non-consumption — and he traces how these entrants “killed” the leader(s) and ended up with the lion’s share of the market. Inspired by a report by Michael Finley, here are a few other examples:

e-commerce. Amazon.com redefined books-selling and beyond. Automotives. When Datsun entered the US market Detroit laughed. Today Lexus gets top dollar. Modular computers. Dell started in a dorm room. Computers used to be large integrated systems. Today computer systems are assembled from interchangeable parts. Handhelds. The Newton was an underpowered flop. Today iPod, iPhone, and iPad rule! Internet telephony. Not good enough before, now VOIP providers such as Skype, are mainstream. Twitter. Competing against non-consumption, Twitter has changed the shape of how we communicate. So has YouTube, for that matter.

Drupal

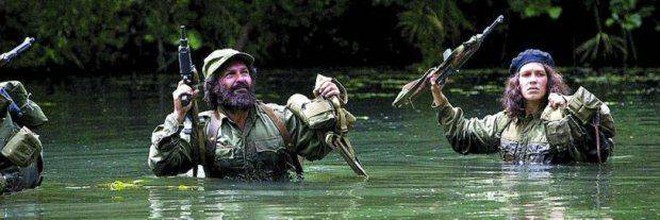

So to Dries’ question: Does Open Source, especially Drupal, represent a disruptive technology? Looking to the bottom of the “food chain,” is Drupal at least a guerrilla? Recall, again, the hallmarks of the guerrilla:

- Find a segment of the market small enough to defend.

- No matter how successful you become, never act like a leader.

- Be prepared to bugout at a moment’s notice.

Find a segment of the market small enough to defend.

Drupal became popular in a small market that was largely invisible. In 2006, when my firm at the time approached Rackspace to provide Drupal hosting for one of our enterprise-level clients, Rackspace said that we were the first firm to approach them for Drupal hosting. A year later, when that same client went looking for venture capital, VC-financing, the folks on Sand Hill Road told the client that they should switch out of Drupal because Drupal was “limited,” “brittle,” “does not scale well,” “rinky-dink,” “too new,” “too small” “unproven,” and “open source.” Ironical though it might be, this dismissal by the VCs meant that the technology was coming in under the radar, so to speak. Like the Borg in Star Trek who ignore “irrelevant” intruders on their cube, Drupal was too small to be assimilated. Thus, if Drupal was a guerrilla, it met the first criterion.

No matter how successful you become, never act like a leader.

By this, Ries-Trout, seems to mean that the guerrilla should not follow the business model of the leader, nor is it advisable to structure the organization in the same way. Be a guerrilla, not a gorilla.

We would have won the war in Vietnam if we could have persuaded the Viet Cong to send their officers to West Point to learn how to fight like we do. Successful guerrillas operate with a different organization and a different timetable.

Be prepared to bugout at a moment’s notice.

However, it does not say you have to bugout.

Disruptor as flanker

I suggest Drupal has started to move from a guerrilla strategy to the flanking strategy. Christensen’s classic case of the steel minimills is the story of the flanking strategy where the guerrilla took the battle to the next step. Briefly: In 1975 minimills made cheap, low profit, low-spec steel, rebar — steel re-enforcing which is buried in concrete. No one expected that the minimills would ever be able to manufacture anything but rebar. The giant integrated mills produced high profit, high quality steel, whose properties were imparted in the rolling process. Since the minimills did not have a rolling process, they were shut out of the profitable sheet steel at the upper end of the market. The integrated mills were not worried. But then, over a period of about 15 years, the minimills continued to make profit-driven technological leaps and they moved from making rebar to making bars and rods, to making structural steel, and finally to making sheet steel. At every stage, the integrated steel manufacturers abandoned the less profitable lines to the minimills and focused on the higher tech, higher margin business. When in the last stage, the minimills figured out how to make sheet steel, the barbarians were indeed at the gate, because the minimill technology was more cost efficient. There was nowhere for the integrated mills to go. The minimills had moved from being flankers to being challengers, to being leaders. The integrated mills were beaten at their own strength. Christensen tells us that “Bethlehem [Steel] closed its last structural beam plant in 1995, leaving the field to the minimills.” p. 105. Most of Christensen’s disruptors more or less fit the Ries-Trout model of the flanker. In Christensen’s case studies, he deals largely with organized firms and corporations that pursue coordinated marketing strategies. In the minimill case the big minimill companies Nucor and Chaparral pursued concerted strategies to go after high profit market niches. Nevertheless, Christensen points out that the integrated steel makers became very efficient.

USX, for example, improved the efficiency of its steel making operations from more than nine labor-hours per ton of steel produced in 1980 to just under three hours per ton in 1991. It accomplished this by ferociously attacking the size of its workforce, paring it from more than 93,000 in 1980 to fewer than 23,000 in 1991, and by investing more than $2 billion in modernizing its plant and equipment.

One logical strategy for the integrated mills was to abandon low-margin segments such as rebar. Professor Christensen tells us:

[the rebar] market was the least attractive of those served by established steel makers. And not only were margins low, but customers were the least loyal: They would switch suppliers at will, dealing with whoever offered the lowest price. The integrated steel makers were almost relieved to be rid of the rebar business…. …The minimills, however, saw the rebar market quite differently. They had very different cost structures than those of the integrated mills: little depreciation and no research and development costs, low sales expenses (mostly telephone bills), and minimal general managerial overhead. They could sell by telephone virtually all the steel they could make — and sell it profitably.

Has Drupal moved from being a guerrilla to being a flanker?

Guerrilla or flanker, the Drupal shops share a lot of similarities with the minimills as described above:

- little depreciation.

- no research and development costs.

- low sales expenses (mostly telephone bills).

- and minimal general managerial overhead.

With Drupal accounting for one percent of websites, and the high profile sites being too numerous to mention, Drupal can rightly be classified as a flanking technology, possibly more.

CMS Wire in cooperation with Water & Stone published the “2009 Open Source CMS Market Share” report, which runs just under 100 pages. The report says that Open Source CMS is dominated by Joomla!, WordPress, and Drupal. Dries in his DCSF keynote reported that 10% of all websites are WordPress to Drupal’s 1%. Yet, is this the ultimate market? Are these top three players just top players in the “rebar” market?

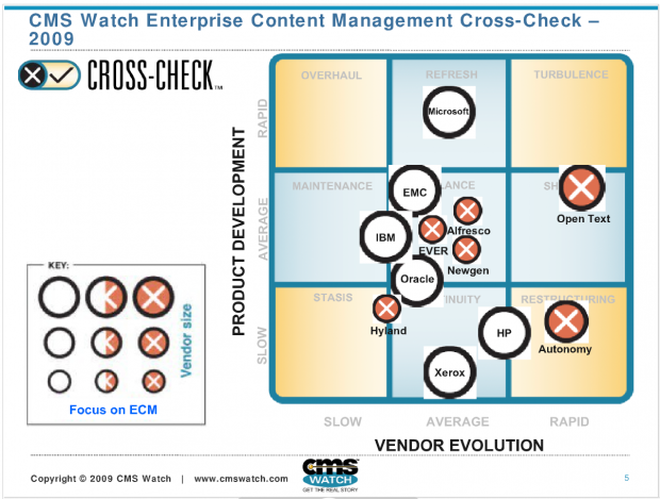

ECM, Enterprise Content Management

At the beginning of this essay, Ries and Trout were quoted, “we’ve never met a company that didn’t consider itself a leader.” Open source is not the driving factor in the enterprise-level marketplace, known as ECM, Enterprise Content Management. This market, with $4 Billion of annual revenue, is dominated by a few key players who are acquiring one another through a series of nine- to ten-figure buy-outs. For example IBM paid $1.6 Billion for FileNet. Documentum fetched $1.7 Billion when EMC2 added them to the corporate family. Just recently Open Text gobbled up Vignette to the tune of $321 Million.

A recent press release from Open Texts describes the firm as earning just under $180M annually, with a customer-base in the tens of thousands, installations approaching 50,000, and millions of seats. Their staff is over 2,000 strong serving over a hundred countries.

Coming Full Circle Until Next Time

To answer Dries’ original question, is Drupal a disruptor? gets down to who it is that is being disrupted. If Drupal sees itself as the market leader against other open source CMS, then Drupal is not. Yet if the ECM players are in the lead, Drupal would be a disruptor. Forrester Research calls the ECMs “integrated players” Their clients are large corporations with heavy database and process management needs — clients who want the “whole solution,” or “end-to-end.” And yet, as the worldwide web continues to evolve, data handling and storage becomes a less erudite field. When the web itself becomes the “whole solution,” the competitive advantage that the ECMs currently have will be less of an advantage.