“Is Japan located on another planet?”

This is what a PhD in physics asked me.

“Why do you ask that?”

“Because in your books about Yamabuki, there are only 12 hours in a day.”

Japan during the Heian period—794–1185 C.E., when the Tales of Yamabuki as well as The Tale of Genji are set—had no mechanical clocks. Nevertheless, to run society, people needed to know the time of day, the season, the month, and the day.

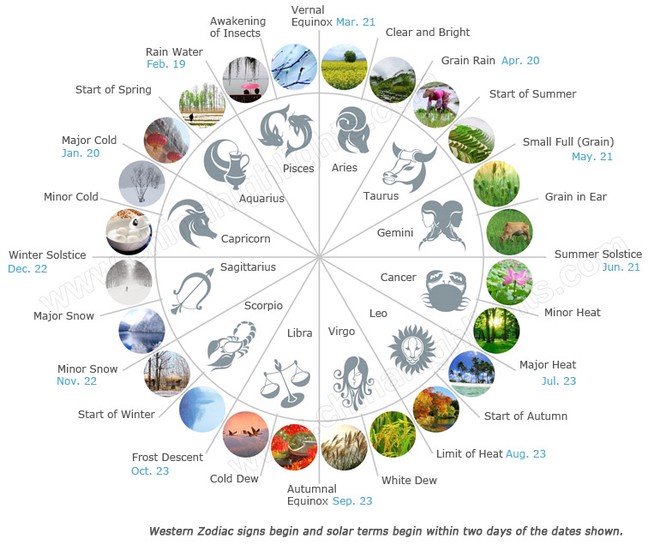

Days consisted of 12 hours based on the 12 zodiac animals, each Heian hour being equal to about two modern hours. In a moment I will get to why I deliberately used the word “about.”

Days were divided into six “hours” of daylight and six “hours” of darkness. Instead of midnight, the day started at daybreak. Only in the Meiji times, in 1867, did the day change at midnight.

What is fascinating is that there were always six “hours” of daylight and six “hours” of night irrespective of the time of year. In modern times, with mechanical and even atomic clocks, we accept that more daylight falls in summer than in winter. We might turn back or move our clocks forward twice a year. In Japan it was done 24 times a year—approximately every 14 to 16 days—so that the first light would always come during the first “hour” of the day, which was known as the Hour of the Rabbit, sometimes called the Hour of the Hare. Dusk would come at the Hour of the Bird, sometimes called the Hour of the Rooster.

If we were to measure the actual length of winter days using a modern timepiece, the Hour of the Rabbit would be shorter than two hours because the relatively shorter total daylight in winter would still be distributed into six parts.

The six nighttime hours in winter would absorb the extra darkness and be proportionately longer than the nominal two hours of our 24-hour clock.

All this kept the astrologers and priests busy, because every 14 to 16 days, the clocks had to be adjusted. “More on that in a minute,” which by the way, is an idiom the Japanese of the era would not have used, because our modern concept of sixty minutes to an hour and sixty seconds to a minute is highly tied to mechanical clocks. The Japanese were no strangers to mathematics and dividing up circles, including the calculus which was independently discovered by the famous mathematician Seki Kōwa, 関 孝和, 1642-1708 C.E., and likely knew enough trig to divide circles into minutes, but they did not parse hours that way–not with the water clocks and hour glasses they used.

The hours were announced by bells of Japanese design which were usually struck by swing a wooden beam again the side of the bell. Unlike Western bells with a clapper, the wooden beam produces a sharp reverb.

Temple Bells of Myoshinji (audio clip)

The Japanese did not number each hour, one thru 12. Rather, they rang the six daylight hours four thru nine, and the six nighttime hours, also four thru nine. We’ll get to the chart in a minute, but why start at four? Some say it was that one thru three bell-strikes were used for various calls to prayers. Others say the three bells informed people that they should get ready start counting—kind of like the “tune” Londoners hear just before the tolling of the hours when Big Ben is operating.

The modern hours ring the graphic, one thru twenty-four. Daybreak in Heian Japan is at six bells, Hour of the Rabbit, and dusk is also six bells, Hour of the Bird.

Interestingly, the Japanese “witching hour” is not at midnight, but at nominally 2 AM (1 AM–3 AM) and is known as the Hour of the Ox. Many Westerners will agree that this corresponds to the biorhythms of many non-Japanese.

To further embellish this, there were five vigils (watches) starting at the Hour of the Dog (five bells) and ending at the Hour of the Tiger (seven bells). The longest tolling of bells in the night was nine bells at the Hour of the Rat, sometimes called the Hour of the Mouse—maybe when “not a creature was stirring.”

That more or less takes care of the day, but the day has to fit into the calendar.

In the Heian period (and until 1867), each month began on the dark moon, also know as the new moon. The full moon would come on the 15th day and the month would end approximately on the 28th, sometimes the 29th, and even the 30th day of the month.

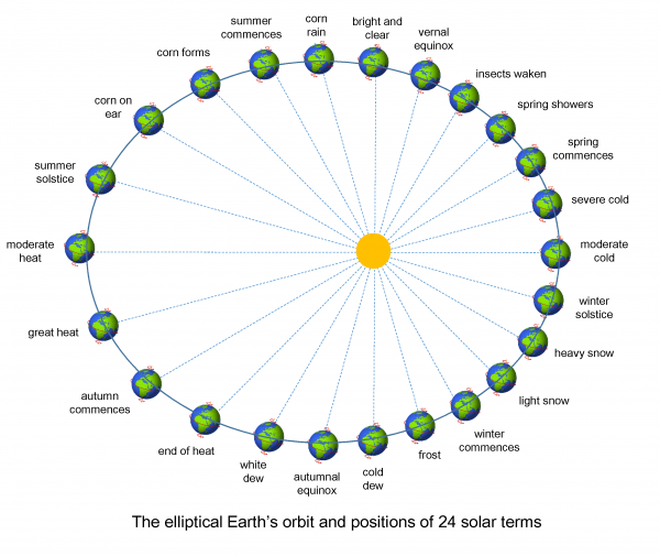

Japanese did not have the western concept of the seven-day week, though they certainly could count to seven. What they had instead was the concept of the solar stem, of which there were 24.

In modern times we are used to a 360-degree circle, which seems quite “natural” to us. Each of the 24 stems would be 15-degrees.

Since the orbit of the Earth, as Kepler uncovered, is not a perfect circle but an ellipse, there are 24 periods when the Earth moves 15 degrees. In the modern calendar, there are 26 two-week periods. This means that a solar stem won’t be exactly 14 days but will be longer by a day or two to stay in sync with the sun. And it is at the beginning of each stem that the daylight and nighttime hours are changed in length to keep it at six daylight and six nighttime hours.

The first solar stem of the Japanese year starts on the first day of the year: Start of Spring, which, unlike the Western calendar, is not in March. The Last Solar Stem (the 24th) ends on the last day of Major Cold. The beginning of the year in Japan, as measured by the Western calendar, would start somewhere between mid-January and mid-February, the variation resulting from aligning the solar stems with the lunar months.

Thus, we know as Yamabuki and Tomoe ride up to the Shayō Tōge, the Sunset Pass, at Sunset on May 11, 1172, in the middle of a freak snowstorm, the author can say with some assurance that it happened at the Hour of the Bird on the 13th day of the 7th solar stem, two days past the full moon of the Flower Month.

If this post gets some interest, I will continue and explain how the author calculates that it is not only the Hour of the Bird, but is also the Day of the Earth Dragon, in the Month of the Fire Tiger, in the Year of the Water Dragon, all of which combine to let us know how well the day is aspected, as well as how it is that some years end up with a 13th month.