Tokyo Shorty (aka Alex Hurst) wrote about the celebration of Star Festival in Japan. Her article is very informative and caught my attention. Her post on Goodreads has excellent details and graphics and was of particular interest to me. She also posts it on her blog. I am working to a deadline of two weeks from today when my first full length novel, Haru, subtitled, Broken Swords, will be going to the professional editor for an line-by-line read with feedback. Star Festival, also known at Hoshi Matsuri, or Tanabata, plays a key role my the plot. In fact, most of the major sections are based around Japanese celebrations and festivals. I had already written this section when I came across her description referenced, above. Thus, I took special pleasure in reading her post and reflecting on the festival. I looked at what she had written and what I had written many months before. In Broken Swords a multi-year drought has gripped the land and the crops have failed. Thus, in my writing, we read:

As the sun settled into the Western vastness, the market day finally ended. A nearly palpable sulk lingered even past the dusk. The day had not been lucky after all. And why would it be lucky? A second monsoon time come and gone without much rain. Nevertheless, this was the night of Risshū: when the stars had moved to their preordained places in the River of Heaven, marking the first day of autumn. The Buddhist monks had proclaimed it was a time of celebration: Hoshi Matsuri, sometimes also known as Tanabata, the evening of the sevens. The bonze had explained that it was called by the second name because the festival fell on the seventh day of the seventh month, but no matter when it fell, or what it was called, or why, none of them could explain how in drought times there was anything to celebrate. Yet, what else could the people do? The holy men had spoken. Grumble though the people might, celebrate they would.

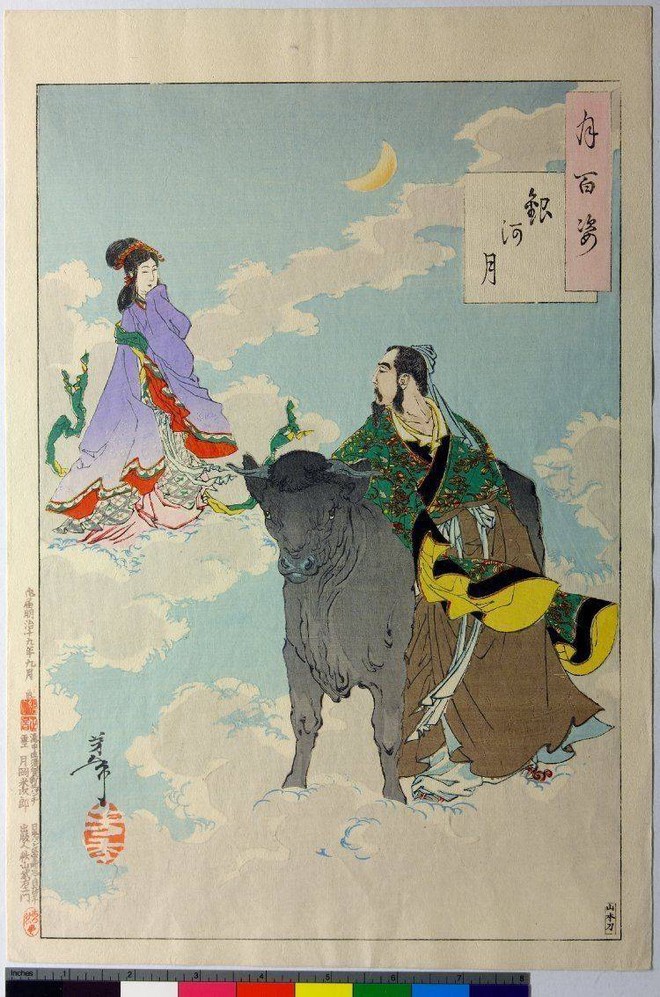

I looked at Tokyo Shorty’s detail about the festival, then compared it to the graphics in her post. Again, from Broken Swords, sword master Ushi has reason to celebrate. He has a mysterious patron.

The sun was fully down. Only the final faint glow of the day remained as Ushi made his way back to the living quarters. He was out of wine. Every flask he had was empty. This problem provided him with his next goal, more saké, and though he felt light headed, he more or less walked straight down the main street to the saké house. Ushi’s thoughts wandered far away, although his feet knew the path to Umé, an easy walk under the uneasy shadow of the ruins of Kuróishiro. He looked up at Black Castle’s massive sheer walls, directly north, that rose above the town like a mountain, and whose feet disappeared into the nearly dry moat that separated the town from the fortress. Though Hōzuki had fallen into the dusk’s penumbra, the top-most roofs of the mountain that was Kuróishiro still caught the last of the sun’s orange glint, looking almost as it did in the days of Lord Inari. Still, Ushi knew, it was but an illusion. The shattered fortress was dead, its heart torn from it. Its walls crumbling in places. He had always felt invulnerable in its shadow. The fortress, a ghost of itself’s once proud self, now seemed foreboding on this autumn evening. “Ah!” Ushi chided himself. This was no way to feel or think. He was rich! He remembered where he was going. To Umé! At the saké house he was sure to find plenty of good company. With his windfall he was sure to find plenty of saké, too. And there would be plenty of women who were willing, especially during Hoshi Matsuri. He was not sure exactly why, but suddenly he longed for Mitsuko. Perhaps it was the memories in the workshop. Maybe it was the mention of his brother, Ichi, and Heian-kyo, but he picked up his pace. Children merrily ran down the street chanting for clear skies: “Tenki ni nari. Tenki ni nari.” Clear skies meant the Herd-boy star could see the Weaver-maiden star across the River of Heaven. And for once everyone was happy with a sky that held no rain, for it mean that tonight would be a time unrequited love would be quenched. “Unrequited love,” Ushi mumbled, again picturing Mitsuko, remembering her in her youth, before she left Heian-kyo, in the Year of the Goat. Ushi further picked up his step as the stars began their show. Braziers burned all along the street. Bamboo cuttings graced the doors of even the most lowly of dwellings. The more affluent householders placed small bamboo trees near their entry ways. Everywhere pieces of paper hung from the bamboo. The papers carried love poems cut into the shapes either of a kimono or cattle. And it mattered not whether one was a gifted writer. Rather it was the intent that counted. Even the illiterate, and that was by far the majority, could get a poem penned by an itinerant priest who also gave a lucky-love blessing upon receiving a coin. If a person had no coin, the priests also cheerfully accepted a donation of food, or even a swig of saké. But Ushi was literate and very rich. He smiled at his circumstances; smiled at everyone and at no one; smiled at passers-by, and waved even to little children, something the sour-faced sword smith was never known to do. The townspeople smiled back and laughed after him for they dismissed all his grinning as a combination of his usual saké habit combined with the chanting, dancing, and songs of the festivities of the evening. Even bitter old Ushi could smile on Hoshi Matsuri. Ushi claimed to enjoy Umé for more than just its saké and women, though there were those who snickered at this claim. For Ushi, Umé still preserved the refinement of the Inari times. Umé’s gates and grounds were invariably well tended so that one always sensed prosperity even in the worst of times; especially in the worst of times. Many a lonely soul sought solace at Umé. Star Festival brought farmers and artisans from every nearby settlement. And on this festival night, the women of Umé hung wind kites with streamers of green, red, yellow, white, and purple. Although the air was still, and the kites drooped vapidly, this did not dampen the festivities in the least. More love poems hung at Umé than at any other structure in Hōzuki, for if someone did not have a true love, one of the nine women of the saké establishment would be more than glad to serve as a surrogate, at least for a modest price. Umé’s wooden screens were open wide owing to the muggy evening and the crush of patrons. Only the interior screens remained closed and it was an open secret why this was so. One patron would exit one of the inner chambers and before long another would be granted entrance. The comely women of Umé were nowhere to be seen, except for Mitsuko, the Mistress of Umé, its one-time Abbess. Ushi’s purse held thirty-seven copper coins, enough for sixteen flasks of saké with five coppers left over to share the pleasure of a lovely Umé girl’s company. The Umé girls charged two coppers, except for Mitsuko who expected five, a trifle…

But things do not go as well as he had hoped, and Ushi returns to his shop, alone to observe the night of carnal love.

In the third quarter of the Hour of the Mouse, long past midnight, Ushi stumbled, flask in hand, homeward through the darkened streets he had negotiated so often before, and drunker than now. Nonetheless, this night seemed especially ominous. Perhaps it was the chill that suddenly fell upon him. When the waxing crescent moon set, Ushi knew the haunted hour approached, the Hour of the Ox, when ghouls and demons rose from the depths of the fearful jigoku. Perhaps the fortress fires gave him pause. Perhaps it was the well-founded suspicion that someone might have followed him; perhaps greedy robbers watched his every move. Ushi imagined hungry eyes hidden in the shadows. His hand slid to his long sword’s hilt. He stole a backward glance, but saw only the darkening dusty street. The clear night sky shone bright with the stars. He pondered: the deserted street proved that those destined to find carnal love had already found it, while those had not, staggered home alone. Ushi looked upward—the Herd-boy star stared across the River of Heaven at the Weaver-maiden star. And despite all his money, for the first time in a long time, Ushi truly felt lonely… He lit the small red jade-brazier that had been shaped into the form of a fox, the last gift from Lord Inari to his Kokaji. The coals crackled and hissed as a thin wisp of pungent smoke rose in the dim light thrown off by the tiny flame. It lit his way to the household Kamidana where he paused, putting the unfinished katana to rest on the kake. He reached up toward a small folded scrap of aging rice paper and its calligraphy. Slowly his strong fingers opened the delicate creases that revealed it was cut into the shape of an ox. His once young hand had effortlessly and unabashedly penned the kanji in a single flourish.

I waited in the autumn wind

To ask you

When will we walk again

Across that bridge of red leaves?

He had meant to recite his poem to Mitsuko at their first Tanabata in Hōzuki, back in the time when Umé was still a women’s monastery, but then, as now, he lacked the courage. It would have revealed too much to her. He carefully refolded the paper, putting it back with the eight successive Tanabata poems he had written to her, one each year, until tonight. For all his dismissiveness, he well remembered how Hoshi Matsuri was to be observed. People arose at the Hour of the Tiger for it was said that night’s sweet dew from succulent leaves made the freshest ink. It was at dawn that he should have set down his vow of love. Now, only under brazier light, he poured saké onto the ink stone to mix it with the ink. “That will have to do,” he thought to himself. Try as he might, he found it difficult to say anything, let alone confess what was in his heart. Still, he picked up a blank sheet of paper and set it down, staring at it. Its stark whiteness, even under yellow brazier light, stared back at him. At once his hand, as steady as ever, flew over the paper.

She is near

And yet so far

With only a broken oar

I cannot cross even the smallest rill

He waited until the ink dried, folded the paper he would never share with her, and placed it away along with the other poems and set the ink and ink stone aside. His love for Mitsuko was as hopeless as the herd-boy’s love for the weaver-maiden. Ushi extinguished the coals. As always, they especially smoked while dying, giving off an odor he associated with endings.

In Japan, Tokyo Shorty reminded us, that Tanabata is being celebrated at this time. However, my date stamp is,

Last Half, Hour of the Bird Waxing Moon’s First Quarter Risshū—First Day of Autumn Seventh Day of Poem-Composing Month Fourth Year of Shōan Year of the Snake Hōzuki Yellow Rock Province The Northern Oku Sunset 6:00 PM August 6, 1174 C.E.

Why was August chosen as the 7th month? According to my charts of Japanese Chronology, in 1174, the year of the action, the first day of the year was (as reckoned by the Western calendar) February 1, 1174. That would have been Dark Moon’s Night. This is under the lunar calendar, which was used until the Meiji times. Hence, the seventh month starts on July 31, 1174 (Gregorian calendar).